Historic Setting

Mathew Bourne chose to set his version of Cinderella in 1940. Inspired by the knowledge that Prokofiev had written the score for the Bolshoi Ballet’s production of Cinderella during this era, influenced Matthew to focus on having World War II as a backdrop to the story.

The classic tale of Cinderella unveils itself set against the horrors of London during the Blitz, and care and attention was given by Matthew and his team, to be historically accurate. (Aside from a few conscious artistic deviations, such as the creation of the American GI, Buster, who appears in the show, though the US did not join the fight against the Germans until after 1940).

Film Footage

One technique used to convey to the audience that the story is set during the Second World War, is the inclusion of news and film footage at the opening of Acts I and III.

Act I begins by showing one of the Pathé newsreels from the day. British Pathé holds one of the finest and most comprehensive Second World War archives in the world, and its inclusion instantly transports us to London amidst the German onslaught.

At the start of Act III we see the beginning of ‘London Can Take It!’ - a short British propaganda film that captured the effects of eighteen hours of the German bombing raids. Intended to sway the US population in favour of Britain's plight, it was produced by the GPO Film Unit (a sub-division of the UK General Post Office), for the British Ministry of Information. Directed by Humphrey Jennings and Harry Watt, and narrated by US war correspondent Quentin Reynolds, this short film was distributed throughout the United States by Warner Bros.

The Blitz

The Blitz was Nazi Germany's sustained aerial bombing campaign against Britain in World War Two. The name ‘Blitz’ - the German word for 'lightning' - was a title applied by the British press to the tempest of heavy and frequent bombing raids carried out in 1940 and 1941.

These raids lasted for eight months and killed 43,000 civilians. The infamous bombing of Coventry on 14 November 1940 saw 500 German bombers drop 500 tonnes of high explosives and nearly 900 incendiary bombs on the city in ten hours of relentless bombardment - a tactic that was emulated on an even greater scale by the RAF in their attacks on German cities.

The scale of the damage to buildings, infrastructure and services, especially in London, though also in other cities such as Manchester and Plymouth was immense.

Whilst initially the government banned the use of London underground stations as places for civilians to take shelter, the residents took the matter into their own hands and opened up the chained entrances to the tube stations.

The East End of London, which housed some of the poorest of the city’s inhabitants, was especially targeted by the bombers because of the dockyards. Most families could do little except stay and see this dark period through and had to adapt their lives to the constant night-time bombing.

Large civic shelters built of brick and concrete were erected in towns across Britain, whilst those with gardens built simple corrugated steel Anderson shelters, covered over by earth.

The bombing raids by the Germans gradually petered out when Hitler began to focus on his plans for Russian invasion in May 1941.

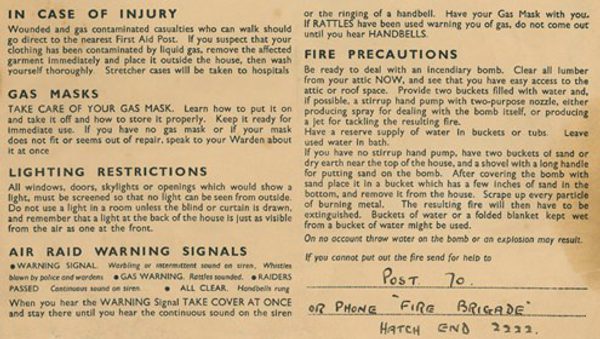

ARP Wardens

ARP Wardens feature during ‘the blackout’ scene in Act I as Cinderella finds herself out on the streets during night of bombing by the Germans, after leaving her family home. Properly known as Air Raid Precautions Wardens, their main purpose was to patrol the streets during blackout, and to ensure that no light was visible. The ARP Wardens reported the extent of bomb damage and assessed the need for help from the emergency and rescue services. These volunteers also helped staff maintain the air raid shelters and were responsible for handing out gas masks to civilians. The wardens were easily recognised by the black helmets they wore with a large ‘W’ on the front. They helped advise people about the safety and harm minimisation precautions, that members of the public were advised to undertake by the government.

Air Raid Precautions cards (as pictured) were sent to homes instructing people what to do during a raid. They told people when to use their gas masks, and how to deal with an incendiary bomb, as well as how to reduce fire risks, and where injured people should go to for help.

Café De Paris

Act II begins with the ballroom scene which Bourne chooses to set in the Café de Paris. Bourne chose to set his ball scene here, since the real-life Café de Paris, (a popular nightclub and restaurant), was the location of a terrifying night of carnage during the Blitz.

Taking inspiration from an article covering that fateful night’s events by journalist Tony Rennell that was originally published in the Mail Online, Bourne used these dramatic events as a catalyst for this dramatic opening to Act II, where we see the Angel ‘re-wind time’ reversing the bombed-out ballroom to its former glory.

Details about that night can also be found on the National Archives website. See the References section at the back of this pack for links to this, and other sources. The Café de Paris remained closed for the rest of the war but reopened in 1948 and is still open today.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

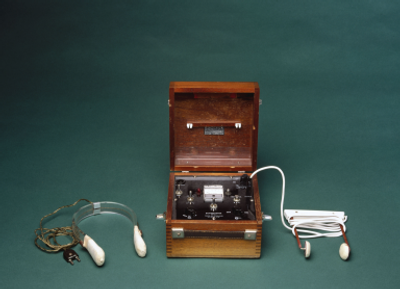

In Act III we see the Pilot rigged up to a machine at the psychiatric unit of the hospital where he is receiving some kind of electric therapy treatment. We imagine he is being treated for depression or PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) brought on by his experiences during the war.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT), sometimes called ‘electroshock’, was one of the most controversial psychiatric treatments of the 20th century.

ECT applied brief but powerful shocks via two electrodes, called ‘paddles’, placed on the patient’s forehead. The technique became widespread in mental hospitals across Europe and North America as it was less dangerous than drug-induced convulsions or comas. Doctors tried it on a wider range of patients. ECT treated severe depression as well as schizophrenia.

Electronics technology advanced during the Second World War, and ECT machines became safer and more controllable, though it remained an aggressive treatment. Mouth guards, bodily restraints and anaesthetic drugs protected patients from being hurt. One unexpected side effect of ECT was memory loss. This included forgetting what happened in the treatment room, which raised troubling questions about informed consent.

Psychiatric drugs became available in the 1960s and 1970s to treat schizophrenia and depression, and ECT became less popular.

Today it is only used in severe cases of depression, where other treatments have proven unsuccessful; or when it is important to have an immediate effect; for example, because someone is so depressed they are unable to eat or drink and are in danger of kidney failure.

"Ectonustim 3" electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) machine, with headset, by Ectron Ltd, England, 1958-1965.

Credits: Science Museum, London/SSPL

Train Station Farewells

Throughout the war train stations became a focal point for traumatic goodbyes and much-anticipated returns, as service men and women left for and came back from active duty.

These highly emotive and often heart-breaking scenes have been memorialised through photos, news footage; and of course, on the silver screen - in movies such as ‘Brief Encounter’ (1945). This British romantic drama film directed by David Lean was one of the films that inspired Bourne’s Cinderella. Similarly, ‘Waterloo Bridge’ – a 1941 film directed by Mervyn LeRoy – was also a significant influence on Bourne. This film recounts the story of a dancer and an army captain who meet by chance on Waterloo Bridge, just after the declaration of World War II.

At the end of Act III we see Cinderella and her Pilot (now her husband) being waved off by the family, departing from the train station to begin their new life together. Along the platform other couples are bidding their own farewells to loved ones.

VE Day Celebrations

The Epilogue and Curtain Call at the end of the show transports us forward in time by several years to the end of the war, where we see all the characters from the show enjoying VE Day celebrations. Bunting hangs from the ceiling and the joy of the people dancing, and socialising, at the festivities is palpable.

Victory in Europe Day, generally known as V-E Day (or VE Day or simply V Day), was the public holiday celebrated on 8 May 1945 - to mark the formal acceptance by the Allies of World War II of Nazi Germany's unconditional surrender of its armed forces - thus marking the end of World War II in Europe.

The term VE Day existed as early as September 1944, in anticipation of victory.

Go Back