Set & Costume

Read our interview with Olivier award-winning set and costume designer, Lez Brotherston. Lez is also an Associate Artist of the company and has worked on many New Adventures productions.

Can you tell us how you collaborated with Matthew on creating the overall design for Cinderella?

I think the process is pretty much the same for Cinderella as it has been with all the other shows we have worked on together. Matthew is in charge of choosing the project that he wants to do. He then comes to me with the title, and an overview of the piece, and we will talk about it.

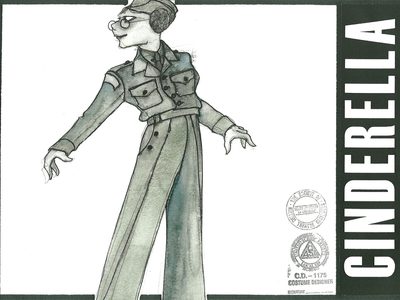

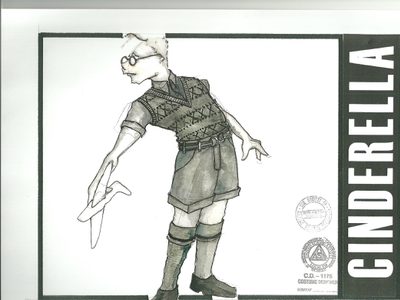

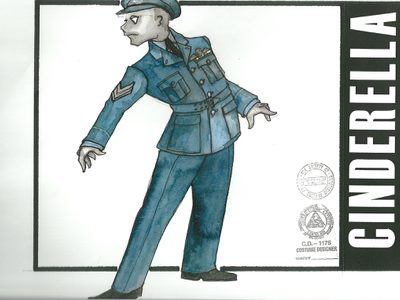

With Cinderella Matthew was keen from the outset not to do a ‘fairytale’ version, but to do a version set in the Second World War, and so that was the starting point for everything. We began by finding locations for the story to be set-in. We then created models of every possible scene, and took photographs of those models, that we could storyboard it; as you would for a film. By offering Matthew something he can then look at it, he can then respond to it.

There is a shorthand that develops after 23 years or so, of working with someone. By fluke we also happen to like very similar things. We both like British cinema, and I suppose really, he knows what I like, and I know what he might like! I know the way he likes me to work is for me to give him a playground in which he can play, rather than for me to be too prescriptive about something.

People often think I spend all my time with the company, and it’s not like that at all. I will spend most of my time by myself at my desk – doing research, making drawings, building models, or having models made, and I might only see Matthew three times. I might email him ideas, or send him drawings to look at, but during those early stages it is pretty isolated process. Later on, you hand those designs over to wig or costume supervisors, and the production manager. It is not until very late-on in the process that the performers come on board, and then you begin to see your designs come to life.

Some of the wigs featured in Matthew Bourne's Cinderella

When you make a moment work, it’s a great personal victory. It’s a wonderful moment when you know you are making the audience feel something particular, that you want them to feel, because of what you are showing them visually.

Not only have you worked on this current staging of Matthew Bourne’s Cinderella, but you also worked on the original production in 1997, as well as the 2010 revival. Can you tell us what changes there have been over the years and what has inspired them?

From memory I think we had four or five weeks to come up with the designs for the original production. And then, when we revived it in 2010 we spent a little more time on it, because we need to take it from a West End production to a touring show.

People who saw the original production might not notice any differences when they see one of the tour shows, but it is significantly different. For example, we didn’t have film in the original production, we had a bigger stage area originally with four bays rather than three, whole sections of the set used to be blue it’s now grey, the floor was blue and it’s now black. If you look at it you might think it’s the same but actually pretty much everything changed, and more detail was added.

It is worth remembering that since you have to commit money and resources to the set, costume and props it is better not to have too long for the ideas stage. Otherwise it’s very easy to go on coming up with more and more ideas, and spending more and more money on creating model after model. It can be very expensive.

The set of Cinderella at the end of Act II, representing the destruction after the Café de Paris bombing

Are there any differences in your working process when working on either the set, or the costumes, or are the methods the same?

It is sort of a parallel process, though I have to say that recently I have started with the characters and then I make a world for those characters to live in. However, it can be different on different projects. For example, for The Red Shoes the idea of the set came first, and then we looked at how we would shift locations during the show.

Looking after the design for one of these shows is such an epic thing to take on however, if you can design ten of costumes and get them out the way, you feel like you’ve got a handle on it a little bit, and you feel like you’ve at least made headway with something! It’s a little like revising for exams where you need to break it down into small chunks. By starting with something easier, you then feel that the mountain has got a little smaller.

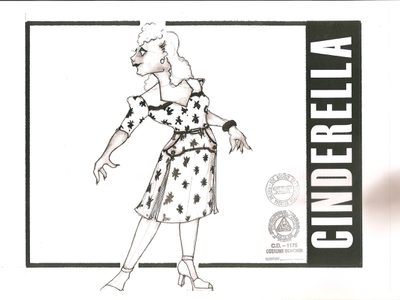

Personally, the drawings of the designs for the principle characters are usually the thing I worry about most. Whereas, if you have to do a policeman that is relatively easy, but when you have to think about what Cinderella might wear for example, that’s much harder.

How much, if at all, are you influenced in your work, by the people that are cast to play the characters, whose costumes you are creating?

Sometimes; but not in the way that you might imagine. For instance, not with Cinderella, and not with the pilot – we knew very definitely what those characters were. However, when you are dressing the cast for scenes such as the ballroom scene, there may be different cast members who play different chorus roles on different nights. And so; there might be a dress that I particularly have in mind for one person to wear for a part, that might be different to what I would want someone else playing that same part to wear on another night. Often chorus members will play several different ‘tracks’, and so what they play varies on different nights.

Characters actually aren’t that useful in the big ensemble numbers - what is more useful is that what those people are wearing suits their bodies. However, when it comes to Cinderella’s mother or her sisters, they will wear the same outfit whoever is playing that part on that night.

How historically accurate are the costumes of the servicemen and women in the show, what kind of research do you undertake for a production like this, and how important is historical accuracy to you?

It’s certainly important in terms of clothes, and make-up and hair, particularly in a dance piece where you don’t have any words. The audience have to be able to look at someone on stage, and now what era the piece is set in, for example. Similarly; they have to know from their visual appearance that they are a sinister character, or they are a good character, and they can only really tell that by what they are wearing and the way they’ve been made-up.

Nicole Kabera, Seren Williams & Kate Lyons pictured in costume

When a show is set during a particular point in history, like Cinderella is, it’s important to really get all that detail right because that’s what’s telling the audience where they are, and what the piece is about.

The research involves a lot of looking at visual references, such as films, photos, news archives etc. Ultimately it will then come down to something that catches my eye, and something that is to my taste. So, I suppose, what I hope, is that my taste comes through, but you wouldn’t know what my taste is.

Lots of dancers and actors would like to be consulted about what their character wears, but I’ve got to have a bigger, overall view, on not only what will be good for a particular performer to wear, but how it all fits together. I have to take the performers along with me, and sometimes they will be wearing something that they don’t like or it’s not to their taste, but it would be the taste of the character they’re playing.

How do you go about finding authentic props and authentic fabric/costume elements to use, for example?

Particularly with Matthew’s shows we make most of the costumes ourselves because they have to be suitable for people to dance in, so it’s a matter of sourcing the fabrics, finding makers, tailors and uniform makers, and also people who are good at making structured couture garments too – and that really comes down to experience in being able to bring the right people on board.

In terms of choosing the fabrics and accessories that comes down to hours and hours spent schlepping round the shops, and sometimes that whole process of looking for the right things can take months.

The set and costumes predominantly make use of dark colours, blacks, greys etc. What was the inspiration for this?

Particularly with Cinderella we tried to make it look as though it was a black and white film. All of the family are all in tones of grey, and that’s what you get what you watch an old film – you might get some white and blacks, but most of it is mid-tone. When we think of World War II we all think of it being in black and white, because of the films and newsreels from that time. It’s always a shock when you see colour footage of London in 1940 because we’re not used to it, and somehow it looks like a very different place – in –fact it looks quite modern when we see it in colour.

In Cinderella the only time we really go into colour is in Act Two when everyone goes out onto the streets and we see the prostitutes, and the rent boys. Even then however, it’s about keeping it in period colours.

I don’t think I’m particularly brilliant with colour so I do tend to limit the palette so I can make an effect with it. I think I’m probably getting better than I used to be, but I used to struggle to know when I put two or three colours together, whether they worked well or were a complete clash!

In all that we’re doing we’re ultimately trying to tell a story, and colour can very much help with that.

Where did the inspiration come from for the red glitter staircase, and also for the white motorbike and sidecar – the vehicle that the Angel uses to transport Cinderella to Café de Paris?

In Cinderella we used to have the couples that we used called the ‘blue couples’ in the ball scene, who come back to life. In the original version, they were blue because they were dead, and their clothes were covered in red sparkles, which was the blood splatter. And so, the red glitter staircase came from that ‘blue and red’ scene. When I later tried to change the colour of the staircase, nothing else seemed to work as well, and so although much of the colouring for the rest of that scene changed, we kept the stairs red, and it has become very much an emblem of the show really.

I think our decision around the motorbike and side-car stemmed from trying to find a vehicle that could do what a carriage does – i.e. if you put people inside it you can still clearly see them. What we’re supposed to be seeing at that point is Cinderella going off to the ball, and so what the motorbike and side-car offered us was the chance to do something a little different, whilst also making sure she and the Angel can be clearly seen by the audience.

Is there a particular scene in the show, that you especially enjoyed creating the design for? If so what is it, and what made you choose it?

I don’t think I have a favourite scene particularly however, there are moments that you feel just land so well in some way, and you really enjoy those. Getting the moment right is somehow more important than getting a particular costume, or a particular piece of set, right. For example, in the ‘grey’ world of the ballroom there is a moment when Cinderella comes down the red staircase in her white and sparkly dress, and for me, it just really works.

Can you also explain how the collaboration works with other members of the design team, such as the lighting designer, to ensure there is cohesiveness between the various elements?

With Cinderella it was fairly easy because we had Neil Austin with us as on lighting, who is very well-respected designer. He hadn’t seen the show before I don’t think, when he came to work on the 2010 version, but he knew it was set in the war and he came and watched rehearsals. I would then sit with Neil in the lighting sessions, and I if there was something I didn’t like. Or I didn’t understand I would just ask, and say ‘why is that ‘cyc’ lit that particular colour at that moment?’. So, I would have that kind of input, where I might suggest that for the hospital scene, as an example, the lighting should be cool rather than warm colours because of the antiseptic environment that the characters are in.

It’s quite hard to talk about light in the abstract so my input happened as Neil was creating the lighting states in front of us. I might say I want a corridor of light, or I want it to feel like a vibrant kind of place, but until someone ‘turns the light on’ it’s very hard to know whether that’s right.

You trained at the Central School of Art & Design, and immediately after graduation began working as a costume prop maker for film and TV projects. You have since gone on to receive both Tony and Olivier awards for your work, and have worked extensively in the UK, Europe and the US. Can you tell us a little about the journey you have gone on, and what advice might you offer to anyone looking to explore a career in design?

I think I was fortunate to train at Central, at what I would say was really a ‘golden time’ for the school. It was a time when I felt Central was the very, very best place for theatre design. The people who mentored us were at the pinnacle of their careers, working in places like the National, for example. And they were people who had themselves, trained at Central. People like Maria Björnson, who designed the set and costumes for Phantom of the Opera, and Alison Chitty OBE, were all ex-students who were having successful careers, and who would come back and critique our work for us. They explained what they felt worked or didn’t work, and why, and so it was a fantastic training.

When I left Central, I did whole operas for almost no money at all, just to get experience. It was very hard to make a living initially and it took me almost 3 or 4 years to get even small rep companies to trust me to do work for them. I’m not sure I ever turned anything down, and tried to do as much as I could, to meet people and develop my skills.

It is hard graft, and to be successful you need to really want to design. It’s not the kind of career that everyone is going to earn a lot of money from. Occasionally you might work on a show where you get a share of the rewards, but I’ve designed more than two hundred shows, and less than twenty of them have ever given me anything back other than the original fee. You of course get the reward of seeing what you have designed brought to life on stage, but it’s not an investment career – it’s got to be something you’re incredibly passionate about, and you want to do.

You have to be a realist too, because with any show there is always a budget, and despite what you might like to be able to do, the bottom line is what can be managed within the budget you have. My foot is very definitely in the ‘arts camp’ and having fabulous ideas about what could be done, but my other foot is firmly rooted in reality, because as a designer you have to be able to make those designs happen.

You will experience criticism about your work, and that can be very difficult. It doesn’t matter how many brilliant reviews you get, it is the bad reviews that stay with you forever. The rewards I have had are wonderful, but actually, what I remember more, will be the thing that someone said ten or twenty years ago even, where they said they didn’t think something I had done was very good, or it didn’t work for them. It is good to understand that it isn’t all highs.

Go Back